The problem is the metaphor

To understand the conditions for more meaningful civic participation, we need to get off The Ladder.

(All these beautiful drawings below were created by Vinay Kumar Mysore)

When it comes to discussions about how to get those who seem to be “unengaged” more engaged with civic life, one metaphor comes up again and again — “the ladder” of civic participation. We decided to dig in to the metaphor, its origins, what it’s really about, and how it’s evolved over time.

The Ladder as You Probably Know It

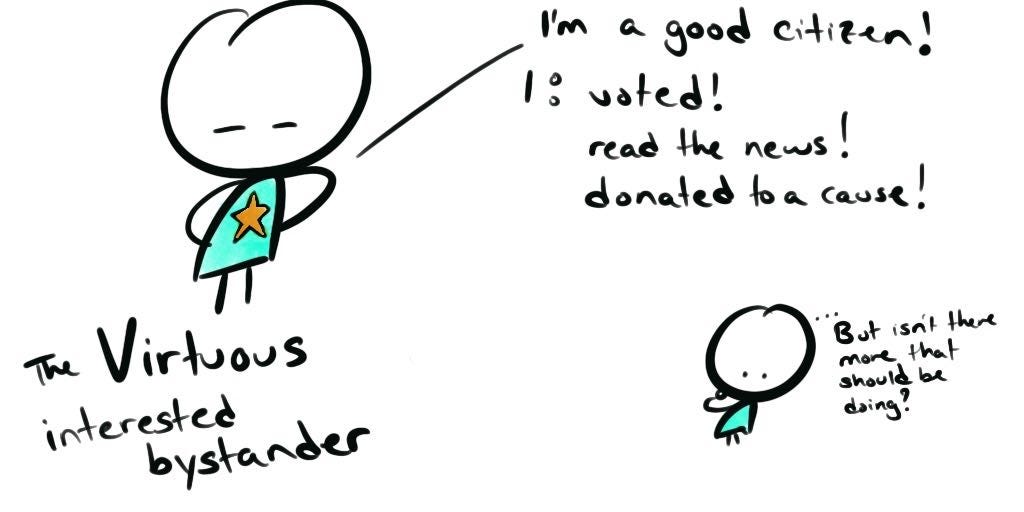

I first explicitly encountered the concept of the “ladder” when someone shared a link to a talk presented at Personal Democracy Forum in 2015 about the “Interested Bystander” in American civic life. The talk outlined research conducted by the Google Civic Innovation Team in 2014 into a large segment of the US voting population who are “aware” of politics and political issues, but who do not regularly express their opinions (in a variety of ways, including voting).

The study was well designed, with a large qualitative sample (101 participants), and a 2000+ response survey, with solid statistical analysis. The method appears to be more informed by user research for tech companies than by social science research or even political polling methods. Regardless, there’s some great data here.

One concept stood out because both the researchers referenced it as part of their analytical frame of what constituted civic participation, and the research participants also seemed to rely on it as a way of describing their behavior: the ladder metaphor of civic participation.

Here’s how the Google team described the ladder:

At the top of the hierarchy is “organizing” — we could put in that box or just above it “running for office”. At the bottom is “sharing an opinion” — one supposes this is mainly about posting opinions online or discussing opinions with friends. It’s important to note that these actions are implicitly political — which is, to Interested Bystanders, by definition “partisan” or adversarial, according to this research.

While this is clearly a framework the researchers went into the field carrying in their heads, it is also something they heard played back by their participants, especially when they described their own levels of engagement as being somewhere on the bottom half of the ladder and aspiring to be higher but lacking the time, knowledge or personal interest to climb higher.

The ladder, understood chiefly through the visual metaphor, is hierarchical and carries with it all the moral judgment of hierarchies (top is good/deserving/virtuous, bottom is bad/undeserving/corrupt). But even if we tone that down a bit, the ladder still conjures an idea of civic participation that we think of as “the achievement model.”

An achievement model is akin to game layers found in half the apps you use, from various quantified self and coaching apps to literally every game. It’s a model that says one of your jobs is to “level up” — to attain new skills, new knowledge, and overcome obstacles to ascend to higher levels of complexity, difficulty or status.

We think this model — one that conceives of civic participation as “achievement” oriented — is damaging. So, where does it come from?

The Original Ladder

The ladder theory is typically credited to Sherry Arnstein. In her 1969 paper in the Journal of the American Planning Association, Arnstein put forth a model that was meant to be provocative. At the surface, the paper outlined a simplified schematic of varying modes of citizen participation, particularly in communities that could benefit from HUD Model City programs in the mid and late 1960s.

The simplest way to ‘read’ the ladder is to imagine that, as a citizen ascends from the bottom of the ladder to the top, institutions relinquish more control to citizens — in other words, at the bottom of the ladder, institutions have all the control and are merely manipulating citizens to go along with programs and policies, and at the top of the ladder, citizens have control over the programs and policies, and institutions are there at most to execute those programs and policies.

But, a deeper reading of this ladder reveals the source of this narrative — a description of a bidirectional system of control.

- The model exposes systems and structures of control by institutions over citizens. What will institutions allow citizens to do? How much or how little do institutions intend to listen and respect the citizens who do participate? How accountable are institutions to the citizens who speak up and participate? What is the history of institutions in relationship with citizens in a community or over a particular area of policy?

- The model simultaneously acknowledges the systems of control by citizens over institutions. What knowledge do they possess? How do they communicate? Who do they represent? How organized are they? How accountable to other citizens are they?

Arnstein was describing a system of control — a system with a history and a location, with tensions between institutions and the citizens in the community, and a struggle over who has control over whom. Because she was dealing with HUD policies and model city programs, she was intrinsically thinking about locality, and about forms of segregation (along racial, gender and economic lines). Place matters, and the history of a place matters, too.

In many respects, her article is a rebuke to institutions “performing” civic engagement at the expense of genuine participation as much as it is an explanation for why some citizens struggle to (or don’t bother to) ascend the ladder from manipulation and semi-public airing of grievances to partnership, delegation and control.

Think, for a moment, of the public hearing as a forum for civic participation. A council sits behind a wood paneled desk on a raised dais, under an official seal. In the gallery, on folding chairs, sit members of the community — still in their scrubs, work boots, gym clothes, uniforms. Between the “audience” and the elected or appointed officials there is often a lectern with a microphone. A member of the public approaches the microphone and provides testimony or asks a question or makes a request. The officials thank the member of the public for their comments and move on to the next person, or the next issue. This whole exchange can be dramatic or dull, protracted or glancingly brief.

It is a noble thing people do — and yet many of us suspect it is largely futile. The council already knows what it will decide, or how its members will vote, or has in fact already decided and these comments are moot. This may be “participation” but it can be merely performative — the governed pretend to have power, and the governors pretend to listen.

Think, too, about the door to door survey administered by a community program. A woman answers a knock at the door. An interviewer with a clipboard presents her with a series of questions with multiple choice, forced choice, or scaled questions. Which of these programs would you like to see in the community? How important, on a scale of 1–10, is it to you? Etc., etc. They complete their survey. Maybe they thank her with a gift card.

“We asked our constituents and they said…” is the opening line of every survey analysis like this — “our constituents told us they would like to install a new playground for small children.” What they don’t tell you is that out of the set of offered choices, this was the one that seemed both to be most relevant and most feasible — but it is silent on the matter of whether this would be the thing that was most impactful to the woman’s life in her community., or the thing she needs the most.

Institutions have a lot of power, and they tend to like to keep it.

Arnstein’s ladder attempts to explain how the various modes of institutions engaging people in civic participation may not be genuine, intended to cordon the public off from participation, or intended merely to look like participation, never letting go of the control that would amount to true participation.

She was working especially hard not to make it about individuals, but about systems of control. The ladder as a visual metaphor was both intentionally incomplete, and intentionally provocative.

Perhaps a better representation of Arnstein’s ladder looks like this:

Eventually the ladder’s visual meaning would subsume the theory itself. It lent itself so well to a story not about systems or control/delegation, but about individuals and their levels of personal achievement. And that, naturally, appeals to those who would rather not address the underlying systems, especially in those non-governmental sectors that seek to influence public policy.

A New Ladder of Civic Participation

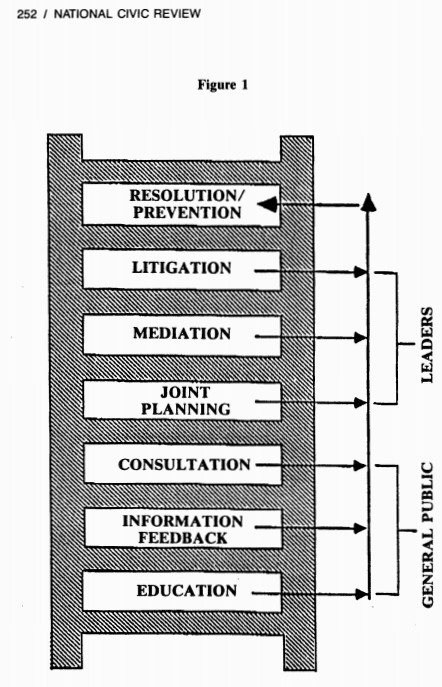

About 20 years later, a consultant named Desmond M. Connor came along to ‘update’ Arnstein’s model.

This ladder explicitly throws over the notion that control should be shared, delegated or relinquished. There are too many significant obstacles, Connor notes, like “the racism, paternalism and resistance of some power holders and the ignorance and disorganization of many low-income communities”. Besides, this should be a predictive model, showing a “logical progression from one level to another, one building to another.” Finally, he suggests that some forms of participation are fine for the general public, but past the level of “consultation”, engagement is better situated among “leaders”.

Perhaps most importantly, he now frames these modes of engagement as instruments for getting a community to consent to a program or policy. If mere education is enough to get the community on board, nothing else is required, and nothing else need be offered. An institution should only level up to the extent necessary to get consent, if not consensus.

Cooper co-opted the visual metaphor, but in so doing, transformed the ladder from a model about communities’ access to control and the dynamics at play with institutions, into a model about a “logical progression” that institutions should allow as needed. A citizen “levels up” only to the status necessary for their consent to a policy or program, and no further.

Later papers would develop this new ladder — adding rungs and other dynamics to it. They might decide to describe it not so much as a ladder, but as a continuum, becoming completely agnostic about any “optimal” rung in favor of multiple points along a spectrum depending on the circumstances.

A story about systems of control had now become a prescription for how citizens should ‘level up’ to higher levels of engagement, and about how institutions should ‘open up’ engagement channels only to the extent necessary to gain consent.

(I acknowledge that this is my read of what these papers are putting across — I doubt the authors meant to be overly paternalistic, they were probably just trying to turn a descriptive model into a predictive one. But the result, it seems, is the same.)

What this means for the Interested Bystander

The Google Civic Innovation Team discovered that Interested Bystanders had internalized a story about individuals and personal achievement. They didn’t need to read Arnstein or Cooper to figure it out. The narratives around elections and campaigns and getting out the vote do tend to pivot around ideas of civic duty and virtue, of some ideal state of citizenship — aware, informed, active, influential. In general, Americans aren’t surrounded by stories about systems — we center stories around individuals overcoming obstacles, doing “the right thing”.

And then there are the campaigns themselves: see an ad to sign up to get updates, then get emails asking for donations or selling campaign swag, then get a text message asking if you’d like to host a house party or attend a training for canvassing, say no to that and get an offer for campaigning you can do in your pajamas, get more emails offering you a chance to win a trip to meet the candidate or attend a debate, and the nearer you get to election day the more requests you get for money, for putting up yard signs, for walking precincts, for calling or texting voters.

But there is always a perceptible border you may not cross — feedback you can’t give, power you can’t have. That is the role of “leaders” — professionals or expert stakeholders. You are, at best, the laity. So, of course people feel like there is “more” they “should” be doing. And simultaneously, there is a reluctance to do that stuff.

Outside the political campaign context though, Interested Bystanders do loads of stuff. They volunteer, attend meetings, deliver food, do things that leverage their expertise or get involved in projects that directly affect their neighborhood or their families. They separate these activities from the political because the experience is more collaborative than confrontational, more social than political.

But they don’t just separate these experiences, they discount them. So do the researchers, by the way, in that they juxtapose this “non-political” civic engagement with more essential modes of civic engagement: voting and debating.

The researchers seem a bit puzzled — and maybe the Interested Bystanders do too — about why citizens will take some actions but not others, why they’ll do all this work in their communities, schools and churches, and then stop at the entrance to the voting center.

The researchers searched for explanations — is it to do with how rooted someone feels in their neighborhood, how important their career is to them, how much time they spend on family obligations? This continues the process of individuating the ladder — making it about particular types of people, rather than about the systems they live in and encounter in their communities.

They point out apparent inconsistencies: Interested Bystanders both don’t take the action they think they should take and undervalue the actions they do take; they say power comes from “having a voice” but prefer not to share their opinions; they think they have the most power locally, but tend not to vote in local elections.

Years ago, for a project involving a video diary exercise, a young mother explained how she worked hard to ensure her 18 month old ate healthy food, as she fed him a spoonful of peanut butter, which he obviously loved. My colleagues were divided — some thought she must be stupid for feeding her kid junkfood in front of the camera while claiming she never would, and some thought that she perceived peanut butter to be healthy, even buying “organic”.

The truth is, people have good reasons, most of the time, for their choices and behavior. The trick is understanding the context for those choices from their point of view, not yours.

Interested Bystanders may not equate “having a voice” with mouthing off their political opinions. Posting political opinions on Facebook or getting into political conversations at work or over the dinner table may not be the same thing as “having a voice”. Maybe “having a voice” is about knowing someone who matters is listening.

“Having power” at the local level may not be something they experience at the ballot box — it may be more likely something they experience when they stop into the storefront of their local legislator’s office, or write a letter, or speak at a public hearing, or shake an official’s hand at a parade. Maybe having “power” is about feeling heard, consulted, seen — and maybe voting doesn’t create that feeling.

Interested Bystanders also report lacking access to people and structures that would enable them to get more involved, or lacking the knowledge to access them. They’re not even sure which entities they deal with are government or private sector — is the city bus government? Is my kid’s teacher government? Is the postal carrier government? Is the county clerk? They’re dealing with high levels of uncertainty about how to get involved, and with whom, where and when, and probably, even whether it’s even possible to get involved. With such a high degree of uncertainty it’s no wonder that “I don’t have the time” is the most often given reason for not getting involved. It’s not merely that they are busy — it’s that figuring out how to get involved seems like a daunting, time consuming, intimidating endeavor.

The problem IS the ladder

What are Interested Bystanders really telling us? Are they telling us that they’re stalled on the ladder of participation? Are they telling us that they don’t equate community interests with political interests? Maybe. But maybe it’s the ladder that’s creating this confusion in the first place.

Interested Bystanders seem to be seeking collaborative action over contentious action. They seek substantive involvement over symbolic involvement. They connect better with matters that affect them personally over advocacy for large groups they may not be part of. They feel more influential locally than nationally.

The political ladder is transactional. It lacks two-way accountability. I sign a petition and forget what it’s even about because do petitions even work? Does anyone have to pay attention to them? I vote but it probably doesn’t make a difference to the outcome, right? These are actions without obvious impact.

At the same time, they are low-risk political actions inside a system that seems both unaccountable and contentious. Signing petitions and voting are small, devotional acts — a way to do your duty and then get on with your life.

So what would happen if we brought back Arnstein and gave her a chance to review the Interested Bystander data? What would happen if we asked people to take all the actions they take under the idea of ‘community’ or ‘civic’ and map them to the ladder they have in their head, the ladder of individual achievement — and then asked them to map those actions to Arnstein’s ladder of a system of control? Which actions would Interested Bystanders call manipulation, or placation, and which would be consultation or partnership?

How might we better understand Interested Bystanders if we saw them not merely as types of people but as constituents in a system of power and control? What if we interrogated more about their experience of place and history and local stories? What would we learn about what feeds or fuels people’s feeling of disconnection from the political?

From a Ladder to a Cube

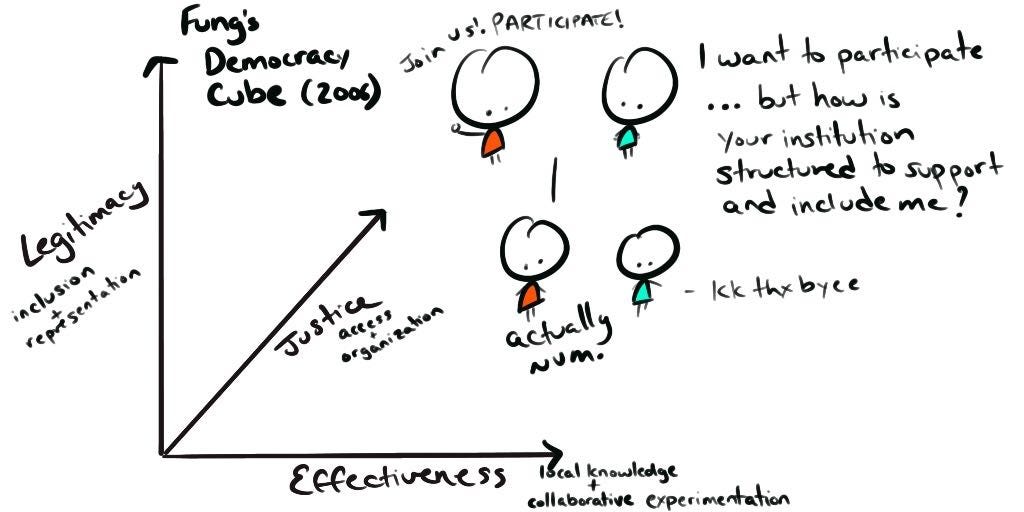

A paper from 2006, by Archon Fung, then of Harvard University, titled “Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance” identifies a different visual metaphor — a three dimensional space for civic participation he calls the Democracy Cube.

Built on dimensions of legitimacy, justice and effectiveness, the Democracy Cube shows how different levels of participation depend on an array of factors — of inclusion and representation (the pillars of legitimacy), of access and organization (the pillars of justice), and of local knowledge and collaborative experimentation (the pillars of effectiveness).

This cube contains the power structures and struggles of Arnstein’s model, the agnosticism about which kind of participation is “best” from Silverman’s continuum model, and conceives of the cube as a three-dimensional map of the people and institutions that should be involved in governance, and the tactics they should use for meaningful and productive engagement.

If Interested Bystanders could understand themselves as being able to opt in and opt out of different styles of participation depending on the issue, would they value their engagement more? Would they punish themselves less? Would they be able to connect voting — that small, devotional act — to other forms of civic engagement where their impact is seen and felt? Would they transform their interest into action they can feel proud of?